Excavations conducted by a team of archaeologists from Birmingham University at South Haven on the eastern side of Fair Isle have uncovered the foundations of multiple buildings very similar to those found on the Orkney Isles at Skara Brae, with a stone drainage and plumbing system and interconnected subterranean dwellings. The Skara Brae settlement dates to around 3000 BC – but the South Haven settlement was established over 500 years earlier. And it was much more advanced. For example:

Sophisticated pottery was unearthed, far sturdier and more versatile, and requiring much higher temperatures to fire than that found anywhere else in the world from that time.

When subjected to scientific analysis, ceramic vessels were revealed to have once contained substances extracted from plants likely to have been used for pharmaceutical purposes unknown until modern times.

There were several small buildings that, because of stone platforms bearing charred charcoal remains, are thought to have been used as saunas 2,000 years before the first sauna was known to have been invented in Finland.

The people of ancient Fairland accomplished something remarkable. They created vitrified sea defenses - walls made from rocks fused together under extreme temperatures to create barriers against the rising waters.

The 350-foot diameter Ring of Brodgar on the Orkney Isles is part of an elaborate arrangement of monuments making up the oldest Megalithic complex in the British Isles. An almost identical complex has been discovered at the bottom of the North Sea to the east of the islands that is at least 1,000 years older.

A Sunken Megalithic Complex

In 2011, in the North Sea off the eastern coast of Orkney’s Mainland Island, scientists conducting an underwater survey using radar and sonar made a remarkable discovery on the seabed: a submerged circular embankment with an inner ditch around 450 feet in diameter, unlikely to have been a natural formation. On closer examination, within the ring were several fallen monoliths around 15 feet long, their regular shape revealing them as artificial creations. When their positions in relation to one another were considered, they appeared to have been the remains of something astonishing: a submerged stone circle around 350 feet in diameter, which may have originally consisted of some 50 to 60 monoliths. Additionally, around 450 feet southwest of the circle were the remains of an artificial hillock 130 feet in diameter and around 10 feet high. All this suggested they had discovered a similar arrangement of monuments to the Ring of Brodgar and its surrounding complex. The stones’ size, number, height, surrounding ditch and embankment, diameter, and nearby artificial hillock were virtually identical. It took eight years for marine archeologists to secure the financial backing to dive and properly excavate the underwater site, and when they did, something completely unexpected was determined. The complex dates from at least as early as 4000 BC – 1,000 years older than the Stenness monuments, the oldest Megalithic complex previously known anywhere in the British Isles. It seemed that the Megalithic culture that first appeared on the Orkney Isles around 5,000 years ago previously existed on what had once been dry land to the east, which submerged when sea levels rose between 5000 and 4000 BC.

The Island of North Doggerland

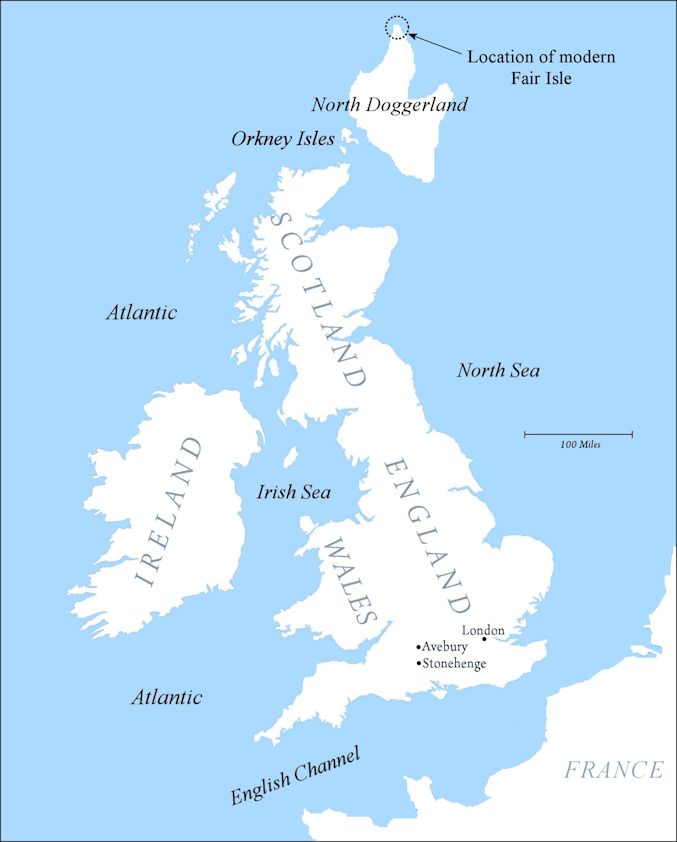

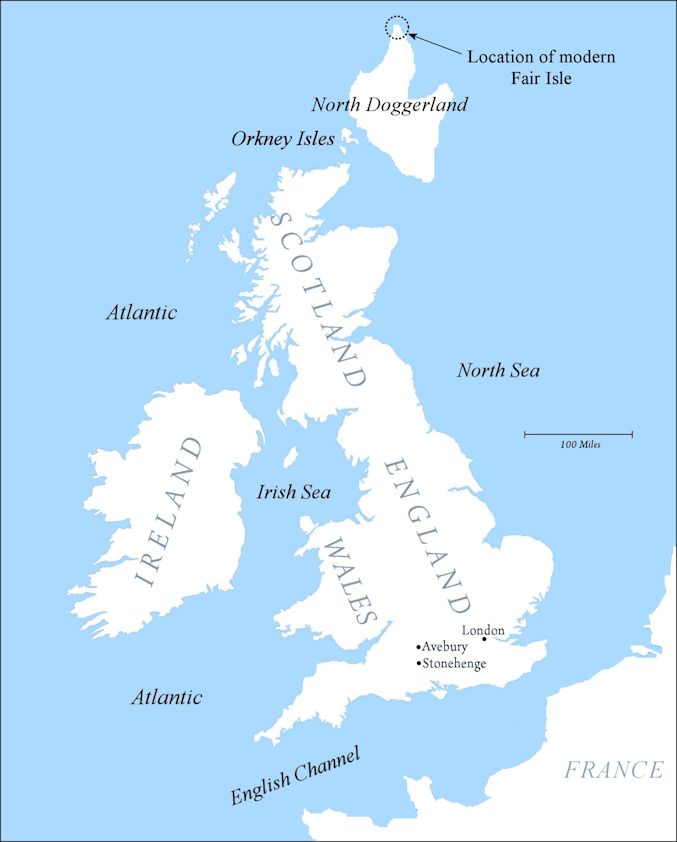

This submerged Megalithic complex once stood on the western coast of an island that was the last area of a much larger region of dry land that had joined Britain to continental Europe, which submerged when sea levels gradually rose after the ice age. The ancient land bridge is known as Doggerland, and by 5000 BC, only its northern part remained above sea level – an island that extended some 50 miles north and 40 miles east of the present-day Orkney Isles, called North Doggerland, on which the complex had stood. The undersea discovery is astonishing evidence that a civilization predating the Megalithic culture must have existed here at least a thousand years before it first appeared in the British Isles. A more detailed survey of the North Sea is needed before we can determine how widespread and how old this lost civilization might have been, but evidence of its sophistication has been discovered on the only part of Doggerland to still survive above sea level: tiny Fair Isle, a remote, treeless island, some three miles long and two and a half miles wide, around 45 miles north of the Orkneys, which had once been an area of high moorland at the extreme north of Doggerland.

The location of North Doggerland and Fair Isle, the only part of it still to remain above sea level.